Nothing prepared us for the desolate, fallen-down beauty that was Havana.

In 1998, I ignored the U.S.'s travel restrictions to Cuba. And I'd do it again.

At the time, my husband Paul's 86-year-old grandmother was ailing there and we wanted to visit her before she died. True, we could have paid $125 each to get special travel visas but we didn't want to give extra pesos to Fidel Castro.

Paul and I also didn't agree with the Cuban embargo. "A true Democracy doesn't tell its citizens where they can and can't go," said Paul. Besides his abuela, many of Paul's relatives still lived in Cuba. They weren't dangerous U.S.-hating terrorists; they were just regular people. People who barely had enough to eat. They were our family.

Maybe the U.S. felt so threatened by Cuba because it was just 90 miles away instead of half a world away. Since Cuba had no resources except sugar cane, I guess they weren't as handy to have as allies like Venezuela or China—countries with even more questionable political practices. But this isn't about politics; it's about freedom.

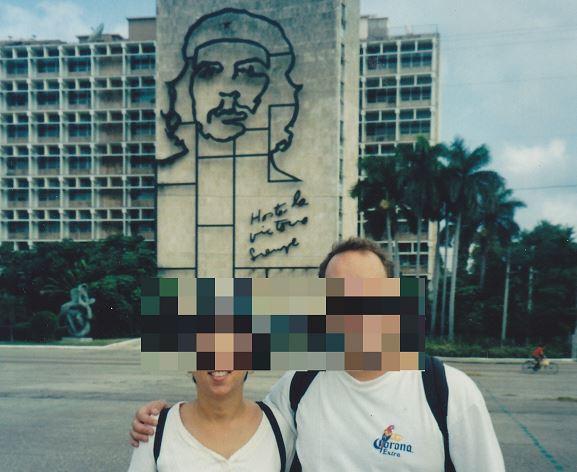

Paul and I went ahead and planned our trip, but not without trepidation. Although violators were rarely prosecuted, technically you can face a fine of $250,000 and 10 years in prison for traveling to Cuba without permission. Which is why I'm writing this anonymously and blurring faces in photos.

Our point of entry was Mexico. If our Cuban dreams didn't work out, at least, Paul and I would get to hang out in Cancun for a couple of weeks. Through research, we knew we wouldn't be able to use U.S. credit cards in Cuba, so we took plenty of cash.

We also took an old suitcase filled with clothes, linens and over-the-counter drugs to give away. Paul's mother, who came to America from Cuba a decade before the 1959 revolution, told us not to bring new things. Although the family desperately needed the goods, they were so poor that it would be too tempting for them to sell brand new items.

It all went as planned in Cancun. From there, we secured reasonable flights on Cubana Airlines. I admit that I was more than a little nervous when we boarded the airplane, a Russian Yak 47. "A Yak isn't the most graceful animal in the world," Paul whispered as the cabin filled with thick, white mist. But we'd been forewarned by a German traveler not to panic; it wasn't smoke but condensation from the clunky air-conditioning system.

Once we safely landed in Havana, our next hurdle was convincing the Cuban immigration official not to stamp our American passports. If he did, we would face serious consequences when we tried to return home.

Even with our pigeon Spanish, the immigration man understood our request and complied without stamping our passports. However, he was more concerned about seeing our hotel confirmation, proving we'd arranged lodgings. But of course, we hadn't because this would require a reservation using a credit card. Instead, I showed him a fax inquiry embossed with the Hotel Ingleterra's logo. He seemed satisfied and waved us on.

Nothing prepared us for the desolate, fallen-down beauty that was Havana: The cars that were older than us, spruced up with turquoise house paint; the buildings that were half collapsed but still regal; the once-grand apartments with crumbling walls and crystal chandeliers. There was music on every street corner, played on battered instruments.

Government-run hotels were too risky, and expensive, so Paul and I stayed with families who had rooms to rent, usually for $15 per person per night. We felt somewhat guilty because we knew we were throwing grandma out of her bed, usually the nicest room in the house. But we reasoned that we were bringing the family much-needed income.

We hired a big man named Carlos to show us around Havana in a Borge, a Russian convertible. Carlos loved to tell anyone who'd listen that my light-haired, light-eyed husband was half-Cuban.

For lunch, Carlos took us to a friend's clean but bare-bones apartment. Juana made us a simple feast of chicken, rice and beans, and charged a reasonable price. But asked us not to take pictures on her Central Havana balcony, afraid neighborhood spies might report her for operating a restaurant without a permit.

The following day, we hired another Carlos (a hunky Antonio Banderas lookalike) to take us to visit Paul's grandmother Neena, who lived with family in Havana's Playa Marinero section. She was tiny and birdlike, but hugged us with a fervor. In no uncertain terms, Neena told us that she wanted a great-grandson, which Carlos translated, blushing.

When we opened the worn suitcase filled with sheets, towels, clothes, toiletries and drugs like Tylenol, I thought Cousin Monica would cry. She couldn't believe it was all for the family. Paul gave Neena a fistful of bills, and promised to return before we left Cuba.

"I'm not coming back," Paul whispered to me on the stairs outside of Neena's place. It was upsetting to see the frail, elderly lady living in such conditions. Her rooftop apartment was basically a shack built on the top floor. With its thin walls and rigid plastic sheeting overhead, I wondered how it could withstand a rainstorm, let alone a hurricane.

For the next few weeks, Paul and I explored the land west of Havana, renting rooms from families, hiring cars that took us from one town to the next. Viñales with its lush greenery and mogotes, reminiscent of China's isolated, steep hills. The unspoiled, deserted beaches of Cayo Jutias. The pristine coral reefs of the island's westernmost point, Playa Maria la Gorda, named for a beloved, fat Venezuelan prostitute. The ancient mahogany bed we broke in a Vedado home just by rolling over.

And the people—Roberto, an aging jinetero (which literally translates to "jockey," a guy who hustles people into restaurants and bars for tips); Alice and Adrian, honeymooning Londoners who were gracious enough to chauffeur us to and from a gorgeous beach; Caridad in Pinar del Rio, who looked out for us like a doting mother; Tim and Ben, the bicycling uncle and nephew from Berkeley who'd run out of money (their check was waiting for us at home in New Jersey when we got back)—were unforgettable.

Despite our fear of getting caught, the richness of experience, the beauty of the land, and the generosity of the Cuban people made the risk more than worthwhile. Never have I experienced such kind, giving individuals. Though Cubans had little, they were willing to share it with us.

I'll never forget when I was plagued by hajene, a type of sand flea whose bites feel like fire. Paul asked a woman who was making us a contraband lobster dinner about the nearest pharmacy. "I could tell you," Gloria said in Spanish, "but there's nothing in it." When she saw me scratching my ankles furiously, Gloria said with pity, "Ai, chica," and proceeded to give me a little vial of antibiotic cream a French tourist had left for her.

Paul and I did go back to visit Neena, the day before we left Havana. The gently-used sheets we'd brought were already on her crude, wooden bed. Paul slipped her more dollars as she hugged him hard, knowing she'd never see him again.

Our flight back to Cancun was uneventful but we had a six hour layover. We decided to pass it at a fancy hotel and enjoy their swimming pool as well as their four-star outdoor restaurant. When I looked at the menu, my eyes filled with tears.

You see, I'd grown so used to a simple Cuban lifestyle with few choices. Typical fare was pollo, pollo e mas pollo (chicken, chicken, and more chicken). Lobster couldn't be bought on the open market—Marxist-Leninist Fidel reasoned that if all can't have lobster, then none can have lobster. Eggs had to be ordered a week in advance.

I stammered when the waitress at the poolside Cancun resort asked what I wanted. I can't remember what I ordered—probably chicken.

Looking back, I'm very happy that Paul and I were brave enough to be rebels and visit this amazing country 16 years ago. I'm glad we did it before Neena died in 2002. Though most of our Cuban family has emigrated to Spain or to the U.S., I would visit again. But hopefully we'll get a chance to go back before Hilton and Disney get their hooks in that beautiful island, take away its charm, and homogenize it.

But this time, we'll take Daniel, the great-grandson Neena predicted we'd give her.

In response to the recent controversy surrounding President Obama shaking Raul Castro's hand at the Summit of the Americas dinner in Panama and everyone being up in arms at the prospect of normalizing relations with Cuba, plus the senate bill to have travel restrictions lifted, I just shrug. To me, this isn't about Communism or Capitalism, it's about people. People who aren't so very different than us.